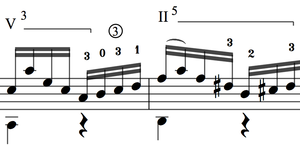

- Image via Wikipedia

© I.Woloshen

Here’s an email I received:

Dear Irene, I play guitar (lefty), just started, and i find it sometimes abit hard to get songs i like (like, by famous people, from the radio, whatever) abit hard to play, because i can’t get the exact tune. So i wanted to start writing my own songs. So i sat down to write some, and i couldn’t. i mean, i wrote a couple, but i can’t seem to accompany my voice (which isn’t very good) with my guitar. i like chords more than notes, so i just go through all the chords i know, just the main ones, and try to fit it together. Anyway, the whole point of me writing, is to say thankyou, you’ve helped me quite abit. But could you please put abit more about putting music with lyrics.

I began writing songs for the same reason you did…I couldn’t play my favourite radio hits! In fact, over the years I’ve met many songwriters who started for the same reason.

When I was in Grade 12, I was given the opportunity to write some music to several poems in the play “Through The Looking Glass”. The idea was that I would play and sing them during the performance with the cast…I was put up in a loft at the back of the stage with a sound system. But the first REAL challenge was writing the music. I had always come from a “music first” place in my songwriting, and never before had tried it the other way around, so when I first sat down with all of these strange poems, I had no idea where to start. After succeeding with one of them, the others came more easily. Here’s what I learned, and what I use to this day…maybe some of it will help you:

1. A song lyric should have a built in rhythm, or “meter”….which means when you read it out loud, you can sense a beat to the words. This will help you to establish the time signature…4/4 is most common, four beats to the bar. Simply speaking, the strum pattern on your guitar should reflect this time signature.

2. Before you even establish the chords, you need to find a melody that matches the lyrics. Don’t go near any instruments until you’ve tried just singing the lyrics accapella (without accompaniment) and found a melody. This takes practise! Look at the structure of the verses…how many lines are there? Are the lines the same length of syllables, or are they different? If you’ve got an even number of lines, say 4 or 6, try singing one melody for the first line, and then another for the second…repeat the first melody for the 3rd line and the second melody for the 4th…see how that feels. Keep it simple. When you get to the chorus, that should be a different melody. Try singing it higher up…the chorus is a kind of climax, if you will, so it needs to be more dramatic in some way. Raising the melody at the chorus is one way of achieving that. If there is a bridge…sing that differently too. Essentially, each part of the song has its own mini-melody, but they all fit together. Creating a great melody is not achieved instantly! Well, not in most cases anyway 🙂

3. Let’s assume you’ve found a melody…now what are the chords? There are several ways you can go about this, most of them take time! First of all, you can randomly look for a chord that “fits” what you’re singing. Knowing a little bit about chords will take you a long way. Is it a sad song? Should the chords be minor chords, or is it upbeat? Do you hear chords around it already in your head when you sing the melody? If you play guitar and have a capo, use that as a means of getting into a key that suits your voice and the melody…you don’t have to play barre chords or fancy progressions, just use the capo up the neck until you find something that’s close. Get yourself a chord book and find out what chords are in a key…which chords go together, in other words. Try out some of the other chords in the key you decide on.

4. When should a chord change? This is where your “ear” really comes in handy. When you listen to a song on the radio, can you hear when the chord changes? If you can, you’re already half way there. Start out simply, by playing one chord all the way through the first verse, let’s call it “Chord 1″…when you hear that the melody doesn’t “fit” that chord, that’s where you should change chords!

Okay, so now you need to find “Chord 2″…look in your chord book at all of the chords associated with and in the same key as “Chord 1″…and try them each out. Most likely, one of them will fit. So now we have “Chord 1” and “Chord 2”. Maybe your verse looks like this:

Chord 1

La, la, da da da, la, la, la

Chord 2

La, da da, la, da da

Is the rest of the verse repeating these phrases? Or are they different somehow? If they are the same, use the same two chords again. If they’re not, try another “associated” chord, or a chord in the same key. Now maybe you’re getting a feel to your song. Use the same process for the chorus, if you have a chorus, and the bridge, if there is one.

That is a beginner’s approach to writing melodies/chords to lyrics…remember to keep it simple! And when it gets “boring”, make a change! No one can write those melodies for you, it is something you learn to develop in yourself over time and with much patience (and sometimes none 🙂 Good luck!

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6926b91f-07a8-493b-bd9e-7cad49545ed4)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=e7760a09-5bc5-4a88-a316-b51083a7f02d)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=44f00a5a-8d9e-4430-92b8-0f6f22b0030f)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=223c3b0a-c5a4-4b09-b1fc-553135d23461)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=20af9406-6126-44dd-b244-cd49ff7f36fa)